August has been connected to the Mission – its grandparents and grandchildren, aunties and nieces and cousins – since childhood.

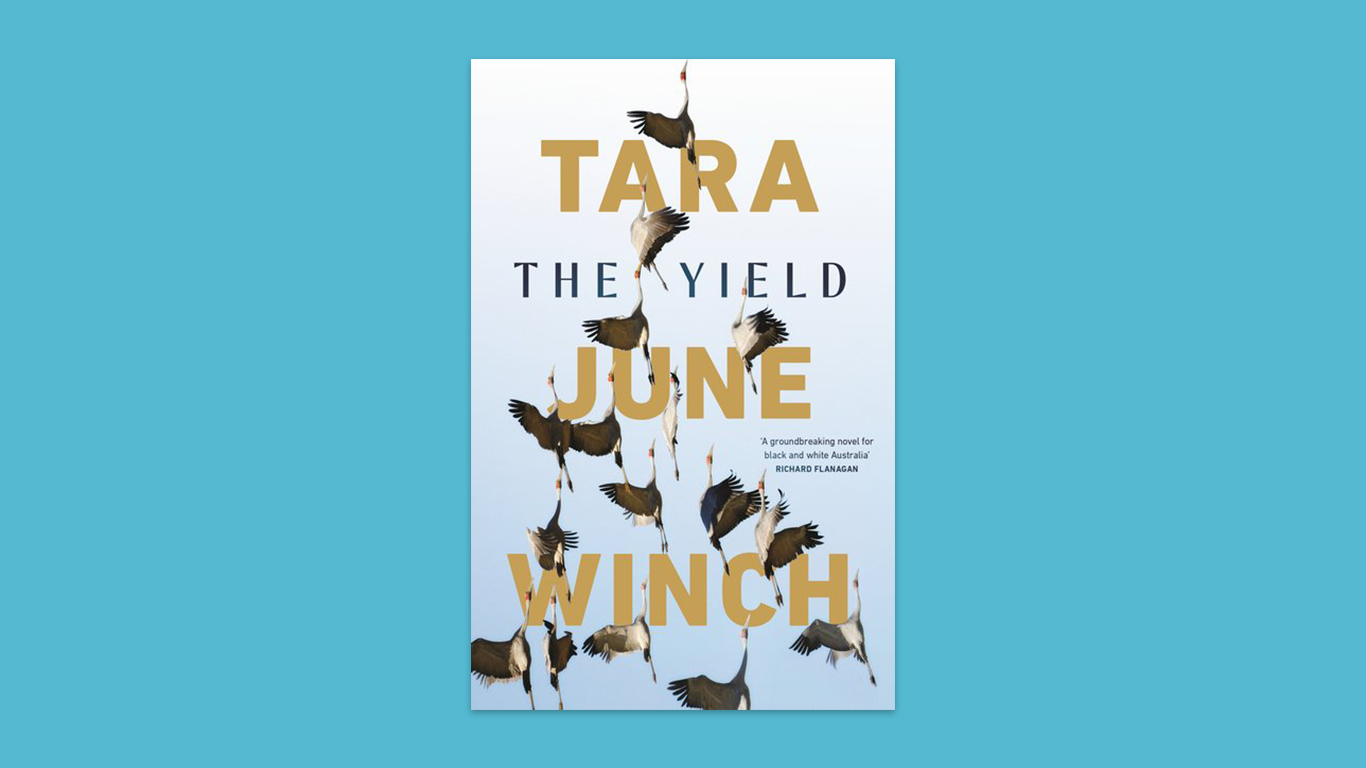

Prosperous Mission is situated on the Murrumby River, a fictionalised Murray-Darling (itself a colonial rendering of the dungula flowing through Wiradjuri Country down to the Ngarrindjeri in so-called South Australia). Because of the things she saw, those things that changed her tongue. How she was scared to leave, even more scared to stay. After nine she could see the little pulleys and gears inside people’s brains, see their skeletons and veins and blood and hearts and the whole of the town’s air coursing in their lungs. She is a survivor of the ‘thousand battles being fought every day because people couldn’t forget something that happened before they were born’, as well as those that came after: anorexia, the sexual abuses of August and her older sister Jedda when they were children, absent parents (they were imprisoned while she was young for cultivating marijuana), and memories of Jedda’s disappearance from the family in mysterious circumstances when they were girls:Īfter nine she could see all the bones of things, the photo-negatives, all the roots of the plants, inside of the sky and all the black holes and burning stars. Having lived in England for the past decade, the prodigal daughter – who didn’t so much leave in disgrace so much as experienced a form of internal disgrace for having left at all – endures ‘a sort of torture of memory comforting like a leech’. When we meet August she is returning to Country for her grandfather’s funeral, and caught in a jag of compulsive recall. In The Yield, Tara June Winch uses three different voices to describe the Wiradjuri people’s journey through ‘executed forests/and hanged bridges’: Elder and compiler of a Wiradjuri language dictionary, Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi, his granddaughter August (‘about to exit the infinite stretch of her twenties nothing to show’), and the nineteenth-century missionary Reverend Ferdinand Greenleaf. The narrator (‘obviously a survivor with obsessive memories’, Czesław Miłosz wrote) registers the meeting as a kind of insult the experience of oblivion, of visceral trauma and fear, make meeting the Mona Lisa, inert, endlessly waiting, feel like a cruel joke: A survivor of the torrential wars and everyday business of annihilation being carried on behind the Iron Curtain comes face to face with Leonardo’s most famous painting, the pièce de résistance of the Louvre and representative of European cultural achievement.

One of his most haunting poems, ‘Mona Lisa’, imagines a visit to Paris. In the poem ‘Mona Lisa’, published in Study of the Object (1961), the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert wrote: Some days it’s not so easy -WAAX, ‘ Big Grief’

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)